Open-source software is a beautiful thing. Whether you’re coding, documenting, giving feedback, etc. there is something bigger than you out there. We live in a time where we can ride the whale wave together, regardless of where you happen to live.

On July 22nd 2016, the Docker community assembled to stress test a release candidate for one of the most exciting versions yet. The following are some notes from my experience and a couple of things learned from this Geeky Friday involving a crowdsourced cluster with over 2200 nodes.

Docker 1.12

The biggest feature (at least for us mortals) in this version of docker is the built in orchestration with swarm mode. Easy, fast and scalable which was just released as production ready this past week.

#DockerSwarm2000 was a project organized by Docker captain @chanwit, with the intent to test the limits of the swarm in huge deployments and give back data to the developers of the engine itself.

The objective of the test consisted on putting together a cluster with at least 2000 nodes contributed by the community, hence Swarm2k. Of course, props to Scaleway who contributed a huge chunk of nodes (1200). Once ready, attempting to execute as many tasks (i.e. containers) as possible, up to the current 100k theoretical limit.

Contributing nodes

Since I had some leftover AWS credit from a hackathon it was a no brainer: I wanted to be a part of this. I don’t deploy nodes to a 4 digit node count cluster every week, and a chance to play with the new swarm CLI commands was interesting enough for me to pull request a 5 node contribution (ended up joining a few more, got caught in the heat of the moment).

I’m not a experienced AWS user, actually DigitalOcean is my go to cloud service provider due to simplicity… Yet another great opportunity to learn something new. I already had a basic set up for the AWS CLI in my laptop, so credentials were all set. Deploying nodes with docker-machine is crazy simple. This was the command I used (embedded in a shell script to loop $i times):

docker-machine create \

--driver amazonec2 \

--engine-install-url https://test.docker.com \

--amazonec2-instance-type t2.nano \

--amazonec2-region aws-region-id \

swarm2k-$i

Joining the swarm

It’s aliveeee! And we had to do almost nothing, @chanwit had already set up everything including a cool Grafana dashboard. We just had to join the swarm:

docker-machine ssh swarm2k-$i \

sudo docker swarm join \

--secret d0cker_swarm_2k xxx.xxx.xxx.xxx:2377 &

Once the nodes started rolling lots of us ran into some problems, including cloud service provider API call caps. Like I said before, it’s not everyday you spin up this number of instances/droplets/R2-D2’s.

When the excitement kicked in, and seeing we were short of the +3000 nodes claimed to be contributed (and kinda close to the 2000 objective) I thought it would be a good idea to spin as many as possible instead of my 5 node contribution.

Considering I was creating t2.nano instances the cost would never exceed my credit with a couple of hours of intense usage. Which turned out to be 342 t2.nano instance hours, or $2.30… Just lol. And it was great, I learned a couple of things from this.

Lessons learned from AWS & docker-machine

So I tried to spin up at least 100 instances, the following are some notes on the process:

- A security group had to be created to open TCP ports needed for the experiment: 22, 2376, 2377, 7946 (TCP+UDP) & 4789 (TCP+UDP).

- AWS has a 20 instance (of the same type) default limit per AZ.

- I created 20 instances in 5 different regions, since using multiple AZ per region threw a weird Network Interface error and I had no to time to work around it.

- Security groups are region specific and I wasn’t able to find a way to “copy&paste” them so they had to be specified manually on each region… That sucked.

- During testing I created and destroyed a couple of instances, which caused a strange error on new instance creation with the same name.

docker-machine rmdoesn’t remove the Key Pair, although this might be due to do EC2 holding on toterminatedinstances for a while after destroyed. Therefore Key Pairs had to be removed manually via dashboard/CLI. - docker-machine/AWS-API struggles with creating too many instances concurrently, therefore the creation script had to create 10 at a time to avoid errors (reasonable IMHO).

Pics or didn’t happen

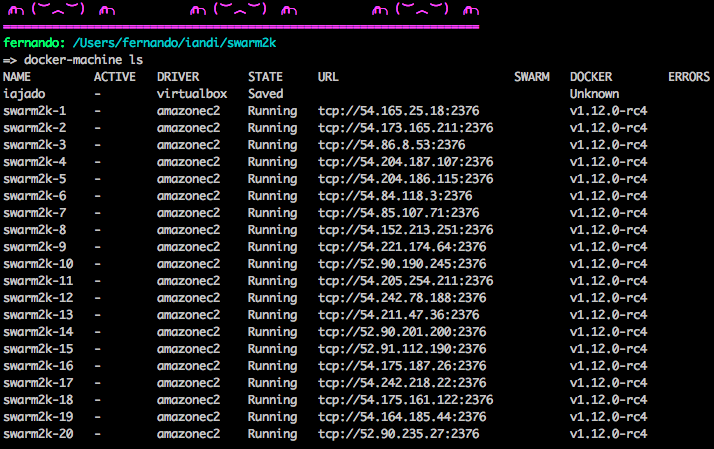

I started taking souvenirs as soon as the instances started rolling. First, after creating 20 nodes there’s docker-machine ls:

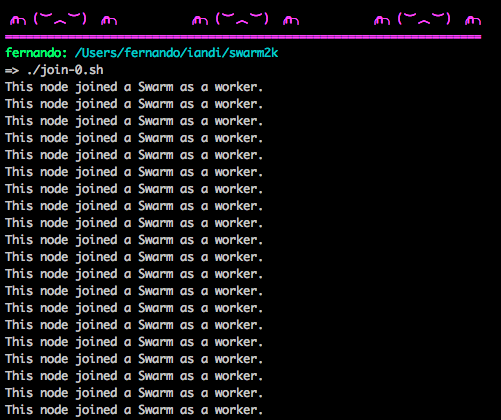

Right after that came the join script of those 20 nodes:

This was so simple and fast it was actually difficult to believe they were actually a part of the swarm. Worth noting that my first 20 nodes were created in AWS eu-west-1 (Ireland) and the swarm managers lived in one of the DigitalOcean NYC datacenter regions.

After creating 100 instances (using all US & Europe regions) and joining the swarm I ran a script that executed the following command (based on a suggestion made by a ninja in the chat room):

docker-machine ssh swarm2k-$i \

sudo docker info|grep \

-e Swarm -e NodeID -e IsManager -e Name

And the output piped into a file gave me a little info about my nodes:

Swarm: active

NodeID: 57vvtuldwcrg949hqgf9n703j

IsManager: No

Name: swarm2k-1

Swarm: active

NodeID: bztszm6s4sohhievpxx5tr3me

IsManager: No

Name: swarm2k-2

...

Swarm: active

NodeID: 5npo4flr76i53d9y7oxnsumao

IsManager: No

Name: swarm2k-99

Swarm: active

NodeID: ane38syyi3cwjargz5wofcaf5

IsManager: No

Name: swarm2k-100

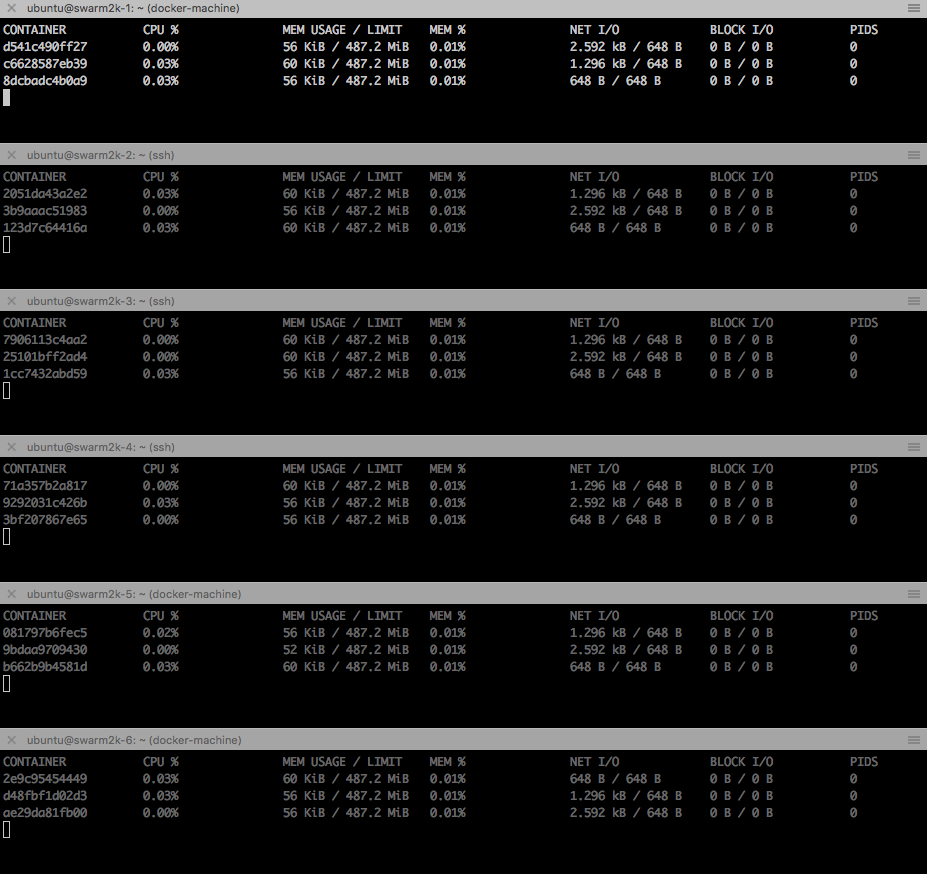

Of course all of us were intrigued. We wanted to know what, how and when containers started to run on our nodes. I ssh’ed into 6 of them and ran docker stats to see what was happening. Containers started showing up:

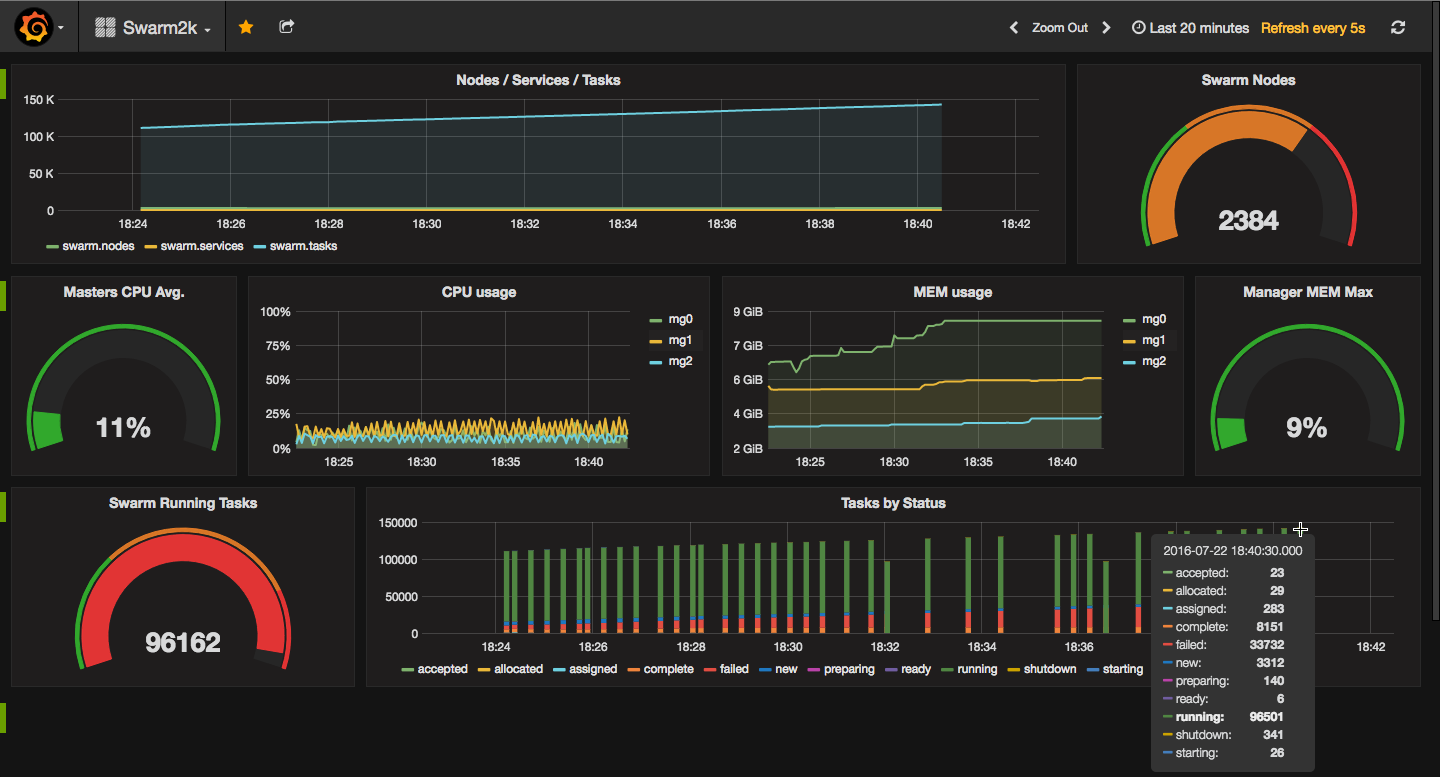

Soon after that I closed all the tabs since too many containers were created to fully appreciate what was happening. I only left my swarm2k-1 stats open to have a peek at it (~40 containers). Finally, the dashboard (i.e. my favorite pic):

Conclusions

Testing the swarm manager leader reelection and scheduling on huge deployments was interesting (and fun). It’s cool (and quite nerdy) to think about the fact that 100 instances of mine spread through 5 different AWS regions were working together with ~2100 other nodes spread over the world.

The swarm team was able to reconstruct the swarm manager and analyze their data a couple of days later. Apparently 100k tasks were NOT able to be provisioned due to scheduling on failing nodes. A hell of a ride and probably one of the geekiest Friday evenings I’ve spent. The Docker team and community haven’t ceased to amaze me since day 1.

Totally worth it, and the experiment gave back something to the team working on these amazing tools we use every day. In case you want to read more about this, @chanwit’s blog post goes through some interesting aftermath of the experiment.

Pura Vida.